China VC: Amicable divorces

Regulatory pressures are encouraging Chinese VC firms to end longstanding US affiliations, but the impact of impending legislation – even sight unseen – cuts deeper into investor sentiment on China

Four years ago, GGV Capital conferred with advisors about pulling apart its one firm-one fund structure. Broader US regulatory powers were poised to extend voiding rights on foreign investments to encompass not only control transactions but also minority deals involving critical technologies. It was not a good time to be a non-American investing in America.

VC firms run by Chinese nationals were in the regulator’s crosshairs and many left the US. Expectations around the treatment of GPs led by a mix of US and non-US nationals were more ambiguous, but some advisors advocated a clean skin approach. Raise separate funds for US investments; domicile them in Delaware rather than the Cayman Islands; only admit US-based LPs; and exclude the non-US partners.

Among investors straddling the US and China markets, GGV was the biggest name to fit this profile. The firm decided not to act, but its limited partnership agreements (LPAs) were amended to allow for an orderly separation under regulatory-driven circumstances. Following the recent issuance of an executive order restricting US investment in China that targets certain technologies, the clause has been enacted.

“There is architecture in the agreement that supports the division of the fund on a regulatory trigger without any need to get consent from LPs. The idea originated five years ago with the concerns about US critical technology deals, but the language is broad enough that any regulatory schism could lead to a separation of US and non-US LPs,” said a source familiar with the firm.

GGV’s latest flagship fund will be broken into two pieces, the source added. This isn’t necessary for the accompanying early-stage vehicle. For the first time, it already comprises separate US and Asian entities.

The firm did not respond to questions about fund structure. Nor did it cite the executive order when announcing the separation of its Asia and non-Asia operations. Yet the timing speaks volumes. If the 2019 reforms that strengthened the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) threatened to alter GGV’s structure, then the executive order – or reverse CFIUS – has contributed to its fracturing.

GGV is not the only firm to announce a separation. In June, Sequoia Capital China said it would sever ties with the US Sequoia entity as part of a plan that will also see the India and Southeast Asia operation become independent. Last month, BlueRun Ventures China said it planned to drop the BlueRun name. It will instead use the established Chinese translation (Lanchi), much like Sequoia (HongShan).

Casting the executive order and the separations as cause and effect is inaccurate (and Sequoia’s announcement preceded the executive order anyway). Rather, they reflect the escalation of an increasingly awkward US-China relationship within venture capital that encompasses not only regulation but also autonomy, territorial rights, past performance, and expectations of future performance.

Even as certain GPs move to minimise any potential fallout for US-based LPs, it is unclear to what extent investors with exposure to China will want to retain it. Many were already of two minds – putting commitments on hold or limiting themselves to select re-ups. The executive order may offer them an exemption as passive investors, but its very existence is just another complication LPs don’t need.

“One of the overriding concerns is that the regulations might continue to evolve. No one knows where the scope will end up, given the changes in US-China relations,” said Doris Guo, a China-based partner at fund-of-funds Adams Street Partners. “You can tell from the fundraising data, some LPs think there’s too much hassle in looking at China funds, especially when they can find similar returns elsewhere.”

Then and now

There are other similarities between 2019 and 2023. The emboldened CIFUS followed the Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA), which focused on industries where technologies are put to sensitive end-uses. Most are irrelevant to VC, but the likes of semiconductors made the list. There was also a clause covering areas that have evolved so quickly regulation has yet to catch up.

Stephen Heifetz, a partner at law firm Wilson Sonsini who previously served on CFIUS, observes that the rules remain “notoriously and grotesquely ambiguous and they intend for that because they want the discretion to say in this situation, we see a Chinese person or some vector of Chinese involvement we don’t like, and we are going to assert jurisdiction.”

He believes the Department of Treasury (DoT), tasked with devising regulations based on the executive order, is “trying hard not to have unintended consequences” and wants to keep the restricted areas narrow. Others echo this view.

Multiple ambiguities must be resolved, including how restricted areas in the three target industries – semiconductors, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence (AI) – will be defined; the criteria under which LPs might be exempted as passive investors; and how different US persons will be impacted. But it is an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking. The actual rules come several steps later.

Back in 2018-2019, legislation was preceded by what effectively amounted to a hit list. A report issued by a US Department of Defense-backed organisation cited seven firms as examples of active Chinese investors in the US: GGV, GSR Ventures, Sinovation Ventures, Westlake Ventures, WestSummit Capital, ZGC Capital, and HAX, a hardware-focused accelerator programme under SOSV.

Several disputed this designation, not least SOSV, which noted that it wasn’t headquartered in China, didn’t raise capital from China, and considered itself American. “Perception is more important than reality, and the perception is that Chinese capital could kill deals,” William Bao Bean, a partner at the firm, said at the time. He added that the US is “pretty much dead” for Chinese VC firms.

Fast forward to February 2023 and Georgetown University’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET) published a study of outbound investments into Chinese AI companies in 2015-2021. It found that US investors had participated in deals worth USD 40.2bn for 251 AI companies. Only one was related to the military. Over two-thirds were classified as general purpose or business services.

GGV was named as the most prolific US investor. SOSV, GSR, BlueRun, DCM Ventures, Qualcomm Ventures, Walden International, Intel Capital, HAX, and GL Ventures completed the top 10. Four months later, GGV, GSR, Walden, and Qualcomm received letters from the Congressional Select Committee on the Chinese Communist Party asking for further details on investments, decision-making, and controls.

Bean did not respond to a request for comment on SOSV being both a Chinese investor in the US and a US investor in China. GGV is said to have responded to the letter and then become overwhelmed by the number of follow-ups. “It’s like applying for an A-share IPO,” said one source familiar with the situation.

Practical steps

As one of the few remaining VC firms of scale investing in China from global funds, GGV’s separation is more complicated than most. Even affiliations with US firms are increasingly rare. Ranking China managers by the size of their most recent fund, HongShan and Matrix Partners China and Lightspeed China Partners are the only ones in the top 10 that share – or until recently shared – names with US VC firms.

Across those three, as well as the likes of BlueRun, Redpoint China Ventures, and DCM, the nature of relationships with the US varies. Sequoia has operated independently, with its own funds and decision-making processes, for years. What must be unwound are shared back office and investor relations resources as well as a global carried interest scheme, according to multiple sources.

This may involve ending single global servers for email and documents – an unavoidable step given maintaining local servers is a requirement under China’s new data security legislation. Global teams offering portfolio services like human resources management, marketing, and business development must be disbanded as well as any global finance functions.

“Even with separate profit centres, there is often one team responsible for finance because everything works to a common standard. Where there is overlap in terms of LPs, the partnership agreements would look the same,” said the source familiar with GGV. “Are there people in China who can produce an annual audit, test it against the partnership agreement, and work with the big four accounting firms?”

As to whether separation makes a China-based team less investable, the level of reliance on the global operation is key. Guo of Adams Street added that independence can sometimes be helpful, citing the possibility of internal conflicts arising between China and India teams that both want to back a Chinese founder who starts a business in Southeast Asia. “Separation removes this issue,” she said.

For the most part, affiliations have largely faded to brand-sharing arrangements. Lanchi claims to have been run independently of BlueRun in the US since 2010. Lightspeed China is said to hold the rights to the name through a commercial licensing agreement that could be terminated reasonably easily.

One manager who retains a branding association expressed a reluctance to end it. Increasingly, start-up founders are nurturing global ambitions and venture capital firms that can help them across multiple key markets are becoming scarcer. The ability to call on resources in the US and China, provided collaboration is limited to that and operations are otherwise separate, has real value, the manager said.

In some instances, however, the risk of negative publicity forces the issue. One industry participant describes VC firms as caught in a bind between Congressional subpoena power – he believes GPs will ultimately be called to testify on their China activities – and China’s data security laws, which preclude disclosure. “Compliance with both will be an impossibility,” he said, hence the rush to disconnect.

Devil in the detail

Once ties are severed, it remains to be seen what must be done to avoid being drawn into the US regulatory web. The DoT’s advanced notice suggests that exceptions could be made for investments seen as more passive in nature, including LP commitments to PE and VC funds. While this might reassure any Chinese GPs with US-based LPs, it does not necessarily absolve them of responsibility.

“In practical terms, most managers are considering themselves to be US persons because their LPs are US persons, and they cannot do anything their LPs cannot do. No matter who needs to comply, someone must make sure the compliance is there – and it must be the managers,” said Lorna Chen, a Hong Kong-based partner at law firm Shearman & Sterling.

The advanced notice indicates there will be criteria determining passivity. Benchmarks could be linked to the size of the LP’s commitment to a fund or the size of the LP itself, given that larger deals are “more likely to involve the conveyance of intangible benefits” typically associated with larger LPs. Chen added that participation on the investment committee or the LP advisory committee could also be a factor.

Irrespective of the independence and passivity issues, Chinese VC firms led by US nationals – of which there are a handful – would be subject to the regulations unless they could recuse themselves from certain decisions without neglecting fiduciary responsibilities to LPs.

Heifetz of Wilson Sonsini takes it a step further, questioning the implications for a US person who must execute decisions taken by others, such as a general counsel who signs off on documents. Moreover, he isn’t convinced the regulatory framework envisaged in the notice would be effective. First, it won’t necessarily stop capital flowing to Chinese companies. Second, it seems too unwieldy.

“Every time an investment is made by a US person worldwide, they will have to check that is either not in the areas covered or not Chinese controlled,” Heifetz said. “If some Chinese nationals create and control a company in Germany, investment would be prohibited. And what if another German company has a Communist Party member on the board? Is that company controlled by the Chinese government?”

Feedback from Chinese GPs managing US dollar-denominated funds is tinged with relief. The scope suggested by the advanced notice is narrower than they had feared, and they don’t believe their existing portfolios, or those of most mainstream peers, will be greatly impacted. In addition, the fact that any legislation will not be imposed retroactively is reassuring.

“I’ve been following this for two years and aggression on the US side has been toned down a lot. I had one slide on this topic at my AGM [annual general meeting] and I spent 15 minutes on it,” said the founder of a VC firm that has no US affiliation but a US-heavy LP base. “I said that knowing is better than not knowing. Many of the LPs agreed. They think China is still investable, but they would like clear rules.”

Clarity would make the dividing line between US dollar funds and renminbi funds, and where they can invest, more distinct. In semiconductors it is already playing out, as evidenced in recent funding rounds. For example, chip designer Enflame Technology recently secured a CNY 2bn (USD 273m) Series D led by Shanghai International Group. Earlier rounds featured the likes of CPE and Primavera Capital Group.

“The industry requires a lot of capital, and the return may not be as quick as elsewhere. Many clients say there are more interesting places to invest in China. In addition, ever since the Chips Act was announced, most investments in semiconductors have been through renminbi funds. The companies don’t want to take new US dollar investment,” said Rongjing Zhao, a partner at law firm Morrison & Foerster.

VC activity in quantum computing is minimal but AI poses more of a problem. The scope could be limited – a small yard with a high fence, which means largely focused on specific military or surveillance end-uses – but Zhao and others expect GPs to respond by raising more renminbi to address AI opportunities.

Unwilling allocators?

The core problem, however, remains one of perception. For every China-based industry participant that plays down the impact of the executive order, there is a counterpart in the US who speaks emotively about escalating risks in the investment landscape and the prospect of Chinese entrepreneurs decamping to other markets to launch businesses away from the geopolitical spotlight.

LP sentiment regarding China is also divided. Adams Street and the US-based Wallace Foundation are still making fund commitments, including the formation new relationships, but they are looking for a higher risk premium, which naturally thins the pack. Wallace has upped the frequency of its China underwriting to once every six months in recognition of the dynamic situation.

Edward J. Grefenstette, president and CIO of The Dietrich Foundation, added that “judging the risk-return profile of China VC is an exercise in speculation” tied to lurking incremental geopolitical risks. He believes most LPs will wait a few quarters and see if the visibility improves. But not all. Another unnamed investor said the China problem is structural and there is no reason to believe in a turnaround.

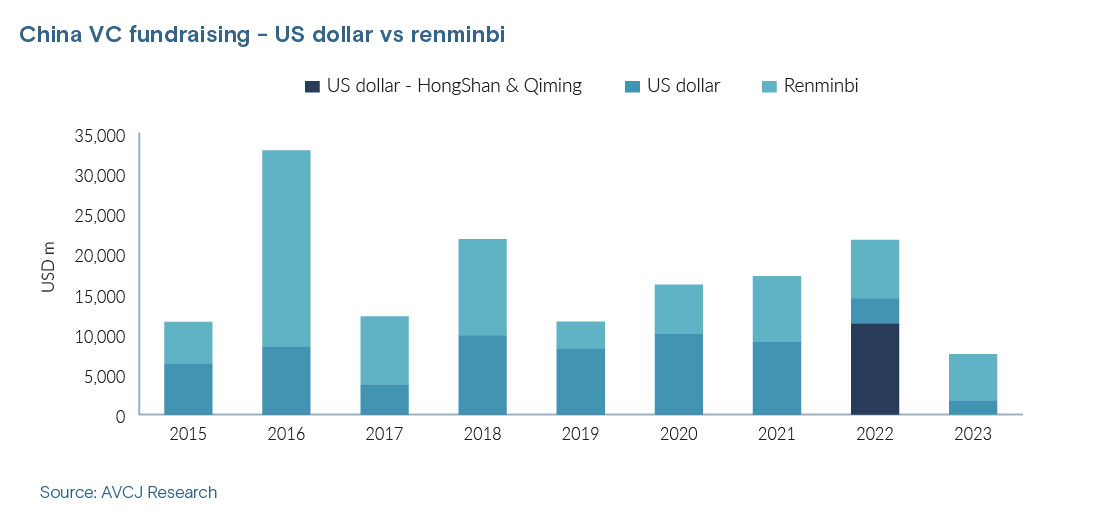

This uncertainty has already filtered through to fundraising. Between 2018 and 2021, annual average commitments to US dollar-denominated China VC funds came to USD 9.3bn. The total reached USD 14.5bn in 2022, but two managers – HongShan and Qiming Venture Partners – account for more than three-quarters of that. This year represents a harsh reality check, with only USD 1.7bn raised to date.

The danger of the executive order is that LPs draw conclusions before the legislation is released and do not change them even if the outcome is favourable. Joyce Zhang, a senior investment officer at Wallace, observed that one of her biggest challenges is presenting China to an investment committee that is already being drip-fed negative headlines through certain media channels. In this context, for institutional investors more broadly, the executive order may just be another reason not to do China.

According to Shearman’s Chen, LPs just don’t want to deal with the executive order issue, even though many VC firms aren’t investing in the sensitive areas. There is “a chilling effect that something is coming,” she added.

However, the true impact is felt in concert with wide-ranging pre-existing concerns. Some of these can be tied to China’s lacklustre GDP growth, declining exports, and weak consumer activity. Others are characterised by more fundamental questions about whether VC performance to date has lived up to the hype.

“Allocations are ultimately driven by LPs’ views of risk and return. If you limit the number of sectors one can invest in, that’s generally a hindrance. Maybe the restrictions are narrow and manageable,” said Lydia Hao, a Hong Kong-based managing director at HarbourVest Partners.

“The bigger risk today is China macroeconomics more broadly – economic growth, consumer and business confidence, and domestic regulation etc. Fundraising has come off so much for China this year because people are unsure. The question is: Where are the returns going to come from going forward?”

To be used for the internal business of the assigned users only. Sharing, distributing or forwarding the entirety or any part of this article in any form to anyone that does not have access under your agreement is strictly prohibited and doing so violates your contract and is considered a breach of copyright. Any unauthorized recipient or distributor of this article is liable to AVCJ for unauthorized use and copyright breach.