News Analysis: Presidential Candidates’ messaging short on infrastructure overhauls

During the current US presidential election campaign, former President Donald Trump and Vice President Kamala Harris have not presented clear strategies for promoting infrastructure development should they win the White House. Eugene Gilligan and Liam Ford ask industry executives what proposals to lower barriers to private infrastructure investment they would like to see from the candidates and the next administration.

While the 2024 electoral race between Vice President Kamala Harris and former President Donald Trump has focused on headline-generating issues such as illegal immigration, the economy and abortion access, infrastructure-focused executives have been monitoring the campaigns closely, listening for proposals to lower the barriers to private infrastructure investment in the US.

To date, neither candidate has discussed infrastructure policy in depth during their campaigns, although Trump’s past administration (2017-2021) and Harris’ work alongside President Joseph R. Biden Jr give some indications of what investors can expect.

What’s on offer

The Biden Administration has made federal infrastructure funding a major focus during its stay in the White House. The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which President Biden signed into law in 2021, authorized USD 1.2trn in spending for transportation and infrastructure assets, while the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provided USD 783bn in spending to expand US energy production and alternative energy capacity, earmarking USD 369bn to energy security and climate change programs, with the goal to reduce carbon emissions by approximately 40 percent by 2030, according to a summary of the bill from Senate Democrats.

While Harris has not mapped out her own infrastructure funding plan so far in the campaign, she proposed during her unsuccessful campaign for the 2020 Democratic nomination for president a USD 1trn infrastructure spending plan that included USD 385bn to upgrade roads, bridges, and public transportation.

Modernizing US infrastructure, or at least criticizing the state of US infrastructure, was a significant part of Trump’s successful 2016 campaign. Trump’s infrastructure plan which he unveiled in February 2018, proposed leveraging USD 200bn in federal spending, that he said would have resulted in USD 1.5trn in infrastructure spending from private, state and local sources. However, his proposal failed to gain traction, encountering stiff opposition from Congressional Democrats during his term in office.

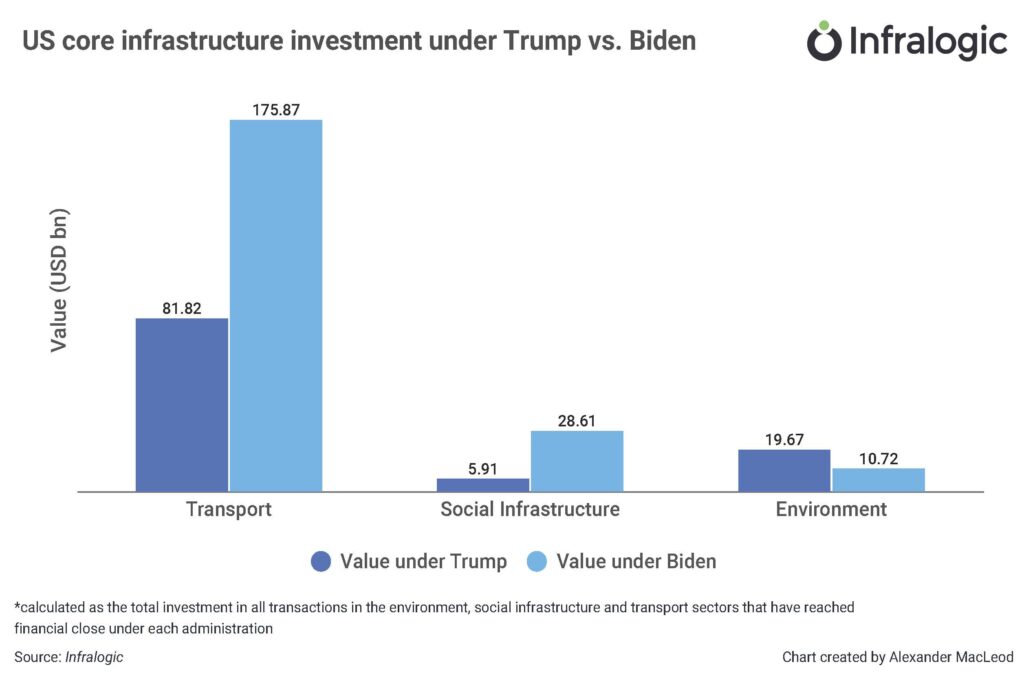

US core infrastructure investment under Trump vs. Biden

President Biden’s IIJA had some positive attributes that lowered project costs, which was particularly important during a turbulent period for the economy, according to Anthony Phillips, Head of Americas for infrastructure developer John Laing.

“Inflation and high interest rates have increased the cost for cities and states to deliver public-private partnerships, so really anything that the federal government can do to offset this helps,” Phillips said.

Specifically, Phillips highlighted the IIJA-mandated expansion of the Transportation Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (TIFIA) low-interest loan program, administered by the US Department of Transportation, which increased project eligibility to include transit-oriented development (TOD) and airport projects.

Another positive aspect of the IIJA is the USD 2.5bn Transmission Facilitation Program (TFP), Phillips said. The TFP, administered through the Building a Better Grid initiative from the Department of Energy, is a revolving fund program “to provide Federal support to overcome the financial hurdles in the development of large-scale transmission lines, and upgrading existing transmission as well as the connection of microgrids in select states and US territories.”

Potential for change

However, Phillips questioned whether we will see continued, long-term support for the IRA and its provisions. While the IIJA achieved bipartisan support in Congress, the IRA encountered opposition from congressional Republicans. “The impact, then, for long-term investors and asset managers, such as John Laing, is that meaningful changes in incentives underpinning investing in these sectors can have a material effect on the performance of the investment, which creates uncertainty.”

Trump has been campaigning on increasing tariffs on certain sectors of international trade, and Phillips noted that “Tariffs can have an impact on supply chains, creating some uncertainty for investors in this period before the policy is clear.”

Fears about a new administration spelling the death knell for the IRA are most likely unwarranted, said John DiMarco, managing director of asset manager Igneo Infrastructure Partners.

“We don’t see a lot of risk of repeal with the Inflation Reduction Act,” DiMarco said. “There are areas of the act that have come under fire, like [subsidies to promote] electric vehicle charging. I think the bigger risk with the change in administration potentially could be the administration of the programs themselves.

“Usually when this kind of incentive or tax-based legislation has passed, it’s generally difficult to overturn. But the ability of the executive branch to influence the way those programs are administered is pretty large,” he said. “The incentive mechanisms under the IRA with respect to the investment tax credit and production tax credit are fairly safe. Those are generally extensions of policies that have been effectively renewed multiple times.”

The IIJA saw an “incredible expansion of opportunity for the states and infrastructure providers in almost every federal program having to do with infrastructure,” Beau Memory, president for North America at Transurban said. “Any future administration should continue to provide the opportunities that the IIJA gave to allow for more infrastructure financing.”

The expansions of TIFIA and the private activity bond (PAB) program were particularly positive, Memory added.

“We would hope that in any future reauthorization or any other transportation funding opportunity that those continue to be enhanced to really support those states that are looking to utilize creative financing and innovative financing to deliver transportation infrastructure,” Memory added.

In addition to keeping both TIFIA and PABs funded, “any work that states and federal policymakers can do to continue to streamline the National Environmental Policy Act process for approving federally funded projects such as roadbuilding, will help meet infrastructure needs,” he said.

Memory believes that consolidating federal infrastructure funding programs and making their uses more flexible could provide better tailoring to each state’s pressing needs.

“Every state has unique challenges, every state has unique opportunities and the more flexibility that can be given to allow them to draw down those federal funds on those particular priorities best suited for the citizens of that state,” he said.

Permitting and reliability priority issues

Project permitting reform and having a stable source of government funds are two keys to sustaining infrastructure development, according to DJ Gribbin, Founder of infrastructure consulting firm Madrus who previously served as Special Assistant to the President for Infrastructure during the Trump administration.

Gribbin says that federal funding has limitations, and does not rank high on the reliability front.

“I would like to see federal incentives for state and local governments to fund infrastructure,” Gribbin said. “We’re drifting, consciously or unconsciously, to more federal funding of infrastructure and, as a result, putting infrastructure funding in an increasingly unreliable bucket.”

“You could actually see the Biden administration supporting renewable projects and pushing those and fast tracking those and the Trump administration taking those off the fast track and putting highways and other things on the fast track,” Gribbin said. “I think what our country needs from an infrastructure policy standpoint is clear predictability and reliability in terms of what the future will look like. But federal funding can play a role. Gribbin says that “there’s been a lot of spigots of federal funds that have been opened for projects, and that could be enormously helpful, particularly in industries that are in transition.”

“If you’re trying to build out an EV charging network, that’s hard to do town-by-town, city-by-city, state-by-state,” Gribbin said. “It’s much more sensible to at least get the foundation of that new system started at the federal level.”

Building a policy agenda

There might be some clues from what Trump favored in his first as to what infrastructure policies a second Trump administration might champion, neither candidate, so far, has talked in great detail about infrastructure policy on the campaign trail.

A major focus of the Harris campaign has been to advocate for the development of more housing, according to Karol Denniston, Partner at Squire Patton Boggs.

“The infrastructure programs have not been as successful as they could have been because the agencies responsible for funding projects have been slow to deploy funds and the public sector needs technical support in connection with project scope and grant writing,” Denniston said. “Assistance with technical support is spotty at best and essential to good use of federal funds.”

A second Trump administration could come with a renewed focus on P3 projects, according to David Schnittger, principal in Squire Patton Boggs’ public policy group.

Schnittger, who served for 21 years on the Congressional staff of former US Speaker of the House John Boehner, noted that Trump pivoted away from P3s after making them one of the focuses of his infrastructure plan. He told some members of Congress “that they are more trouble than they’re worth,” Schnittger said.

“The Trump backers’ take on the Biden infrastructure plan is that it took roads and bridges to the bottom of the pile, in favor of multi-modal transportation projects, and their take is that we can’t build new roads and bridges, due to the limitation in the law regarding the high environmental bar that has to be met,” Schnittger said.

An initiative designed to “close that gap” could be part of a second Trump administration, he said.

“You have people in his orbit, not necessarily speaking for the campaign, but who have put policy prescriptions out there, who have long seen P3s as a useful tool to get these types of projects done,” Schnittger said.

“If you really want private investment in infrastructure to occur, you need to have projects that are capable of achieving an investment grade rating,” according to Shant Boyajian, partner at Nossaman. “So, anything that would impede that, will have a corresponding chilling effect on any private investment in infrastructure. One way to think about it is, how to incentivize private investment by reducing the level of risks in these projects.”

Regulatory risk is one area that the candidates will have some influence over once they are in office, Boyajian said.

“One of the things that the candidates should push for is for the environment to be protected, and the impact of projects identified and mitigated, while still allowing those projects to move forward,” he said. “That will provide predictability to projects, and more certainty to investors.”

He believes the candidates should also commit to support reauthorizing the IIJA.

“The IIJA will expire in the next presidential term,” he said. “The candidates should commit to supporting it with long-term reauthorization of those programs at the funding levels established by the IIJA. That will demonstrate to the private sector the federal government’s commitment to modernizing public infrastructure.”

The US is not seeing “pure revenue-risk projects,” Boyajian said, noting that most projects have some element of public funding. “A long-term reauthorization of the IIJA will ensure the ongoing availability of public funds needed to facilitate projects that are ripe for private investment,” he added.

Leading from the states

While questions persist about what a second Trump term or a Kamala Harris presidency may favor in terms of federal infrastructure policy, there is some positive news on the state level for P3s. A pipeline of managed lanes P3 projects in Georgia and Tennessee has sparked optimism among some developers and investors.

“Georgia and Tennessee have announced consecutive P3 projects to address traffic congestion,” Phillips said. “This provides confidence to the private sector that there is a pipeline of opportunities, rather than one-offs. That’s important, given the resources that are required to pursue P3 procurements.”

There is also positive news on the state legislation front, according to Michael Albrecht, managing partner at asset manager Ridgewood Infrastructure.

“A key policy that we believe empowers cities is the recent legislation passed in Florida,” Albrecht said. “The legislation provides cities more flexibility to choose the specific P3 process they believe is appropriate, for example, avoiding costly aspects if they already have a competitive process. This flexibility provides a transparent and efficient process which benefits all stakeholders.”

Some state legislatures are “re-looking at their P3 statutes to see if they need updating,” Boyajian said, citing Washington State as one example.

States such as Georgia and Tennessee see P3s as a tool to manage significant, local infrastructure issues and the infrastructure investor community will be watching to see if the candidates’ platforms will support this positive momentum.