Trump tariffs excite interest in the art of the defensive deal – analysis

- Defensive M&A to maintain market access across trading blocs

- Mixed views on scale of possible EU-China rapprochement

- Chinese EV production, tech transfer in EU expected to grow

Global dealmakers have been remarkably optimistic since the US presidential election result, which returns Donald Trump to the White House.

Beyond relief at an uncontested election result and the apparently inevitable bonfire of Wall Street regulation, including a much more accommodative approach to mergers across both the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, the enthusiasm of dealmakers outside the US may at first glance seem perplexing.

Most economics textbooks would tell you Trump’s protectionist agenda can only be a net negative for global growth and, consequently, corporate activity. Trump’s appointment of Cantor Fitzgerald founder and fellow tariffs devotee Howard Lutnick as Commerce Secretary appears to dial up the likelihood of a trade war.

But deal practitioners around the world seem to believe the hastened fracturing of the neoliberal order heralded by a “Make America Great Again” (MAGA) administration will, in turn, accelerate multinationals’ plans to maintain market access across trading blocs by undertaking defensive M&A, often in search of “Made in America” tags.

“A lot of companies will want a broad footprint,” according to David Henig, Director of the UK Trade Policy Project at the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE).

If there are tit-for-tat tariffs from the US, the European Union (EU), and China, that’s “economically not ideal”, but “wealth capital is largely uncontrolled versus goods,” Henig said.

That means companies would be able to use cash to buy overseas operations in tariff-levying territories.

In other words, companies may avoid import duties if Trump and other blocs’ focus is largely on final goods – allowing the import of parts, say, to the US from Germany, so long as the end product is assembled in America. Not only that, they would also find that amassing jobs in territories raising tariffs will likely provide political cover from executive fiat, Henig suggested.

EU-China rapprochement?

If multinational companies need to consider organic growth or M&A in other blocs to ensure market access at reasonable terms, the next question is: can we predict the likely flow of capital for those deals in advance of 20 January 2025?

Some market participants like to think so, suggesting that Trump’s trade hawkishness on China and antipathy to the EU could push the latter together in an uneasy embrace.

As this news service reported earlier in the month, panelists at IPEM China 2024 – speaking just after Trump’s election had been confirmed – said they were optimistic that cross-border deals between Europe and China could be on the cusp of a rebound. Trump’s re-election coincided with a USD 1.4trn Chinese investment plan to spur sluggish economic growth that is expected to translate into more investment in Europe.

Indeed, Europe will probably continue to be a conducive environment for Chinese outbound investment and M&A deals in the new context, according to Drew Bernstein, co-chairman of MarcumAsia.

Dealmakers are likely to see a greater focus on European policymakers regarding employment, local investment, and technology transfer but with fewer concerns about national security issues, he suggested.

There’s more. President-elect Trump’s aggressive approach to “rules of origin” where China is concerned – i.e. not only final goods but also the raw materials and parts that make them – will likely make it challenging for Chinese electric vehicle (EV) producers to establish assembly production in the United States, Alicia García-Herrero, Chief Economist for APAC at Natixis and senior fellow at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel, said.

Consequently, Chinese companies may mull EV production in the EU, as the latter’s own tariffs on EV imports from China “look much smaller now” versus the Trump administration’s, García-Herrero said. Chinese manufacturers will try to produce final goods in the EU, she argued.

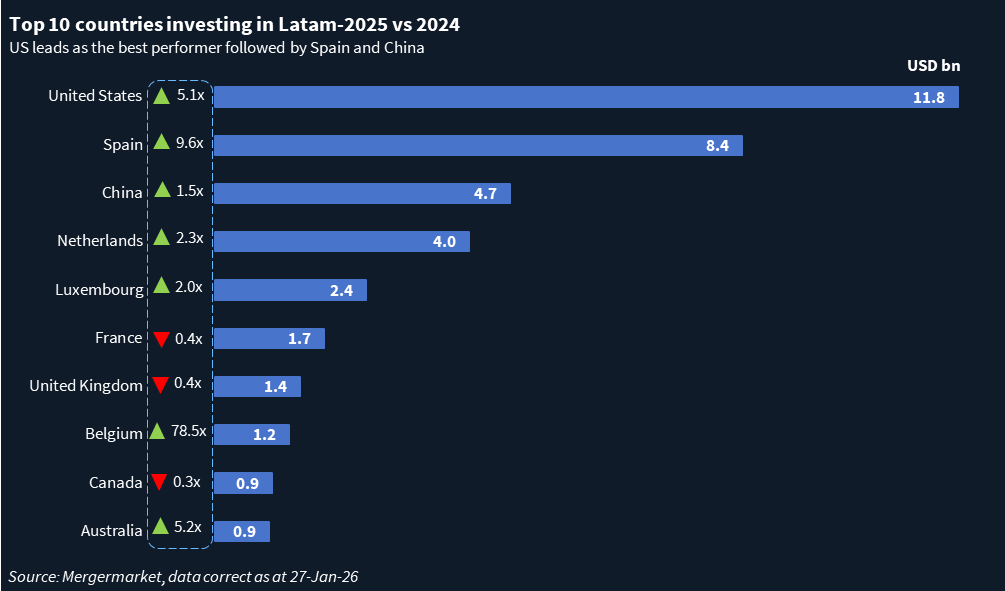

You can have a decent crack at sustaining optimism about China-into-Europe M&A by checking out the stats: the value of Chinese buyouts of European assets has climbed 48% thus far in 2024 to EUR 9.4bn across 53 transactions, compared to FY23, according to Mergermarket data.

There is nonetheless caution. The EU cannot afford to lose the US as an ally and economic partner, Henig said. The core scenario is that the EU will at least remain as firm as its current stance on perceived Chinese goods dumping and could go further to placate the new regime in Washington, he suggested.

Indeed, in European Commission confirmation hearings before the European Parliament over recent weeks, both Kaja Kallas, the commissioner-designate for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, and Maroš Šefčovič, the commissioner-designate for Trade and Economic Security, have adopted a hawkish stance on China.

The EU’s Foreign Subsidies Regulation (FSR) was clearly devised to mostly respond to issues around Chinese state subsidies in merger reviews and won’t come to a halt, even though the European Commission’s stance on safeguarding competition can evolve, a Brussels-based competition lawyer said.

Competitiveness conundrum

In a report on competitiveness for the European Commission published in September, former Italian premier and European Central Bank President Mario Draghi called on the EU to “restore its manufacturing potential”.

Before any considerations on softening its stance towards China or boosting M&A with the US, industrial sovereignty should remain the EU’s key priority as tariffs kick in globally, one Paris-based lawyer agreed.

The central conundrum is that building this capacity – so that the EU can compete with China – will require a considerable amount of Chinese tech and resources, Henig said. Europe needs access to crucial technology across the energy transition and industries such as EVs, telecommunications and artificial intelligence (AI), a deal lawyer said.

In this context, neither the US nor the EU can be said to approach the question of China “in good faith”, Henig argued. The EU has placed significant tariffs on the import of Chinese EVs, but has been less concerned with, say, washing machines, he noted.

The protectionist impulse is intense in areas considered vulnerable or strategic, but everyone acknowledges the continued need for Chinese imports, Henig said.

Indeed, the EU will introduce new criteria in December when Brussels invites bids for EUR 1bn in grants to develop EV batteries, requiring Chinese businesses to establish factories in Europe and share their technological expertise, the Financial Times reported yesterday (19 November).

This Janus-faced approach to Chinese imports and investments is likely to be picked up in Beijing.

But with the US offering better growth prospects than Europe, the biggest trend for well-funded, multinational European-listed companies may not involve China at all, but making acquisitions stateside, two France-based M&A advisors said.

Perhaps corporations will focus more, before Trump takes office on 20 January, on corporate restocking ahead of potential tariffs. Maybe, even after that, there will be a holding position to see exactly how the once-and-future president’s agenda truly shapes out beyond his rhetoric.

Nonetheless, Trump’s re-election turns the page on the prospect of reviving the “Great Moderation” and the international rules-based neoliberal settlement embodied by institutions such as the World Trade Organization.

Dislocate a shoulder and it’ll be deeply unpleasant for you, though rather more lucrative for your physician. Dislocate the global economy and not all will benefit – but for those picking up the pieces and refashioning the landscape, there could be spoils aplenty.