European bank M&A pipeline stacked as rates, scale, tech drive deal flow

- 30-40 active European banking deals eyed in next six months

- Cross-border deal attempts highlight intent despite risks

- Macroprudential, competition regulators more accommodative

It’s been a fool’s errand in recent years to predict a wave of European bank M&A. Overbanked, lacking scale and losing ground to US and Chinese lenders in the global league tables, the case for European consolidation is strong – but regulatory headaches, political concerns and board inertia have limited efforts to seize the obvious solution.

Not anymore. A slew of bold tie-up efforts – including on the cross-border front – have revitalised sentiment.

Rainmakers have told Mergermarket that a softer interest rate environment, a more accommodative regulatory landscape, geopolitical turmoil, the pursuit of tech supremacy, and a flywheel effect, as deals materialise, are driving a strong pipeline for the rest of 2025 and beyond.

“For the next six months, overall, we see an active pipeline of 30 to 40 active situations in the banking space across Europe,” said Ronan O’Kelly, Head of M&A Europe at Oliver Wyman. “There is a real chance of a snowball effect, as many credible bidders chase a few attractive targets,” he added.

Deals create momentum, noted Christopher Sur, Global, EMEA and Germany Financial Services Deals Leader at PwC Germany and author of its global M&A financial services mid-year report.

“They raise questions from shareholders to their boards – ‘has the train left the station?’ As a professional advisor, it’s not only hope but rational that we envisage momentum,” he added.

Further European bank consolidation “seems inevitable, with scale, capability enhancement and diversification being the likely catalysts”, Scott Kirkby, Managing Director in Houlihan Lokey’s European Financial Services and Technology team, added.

That has certainly been true so far this year.

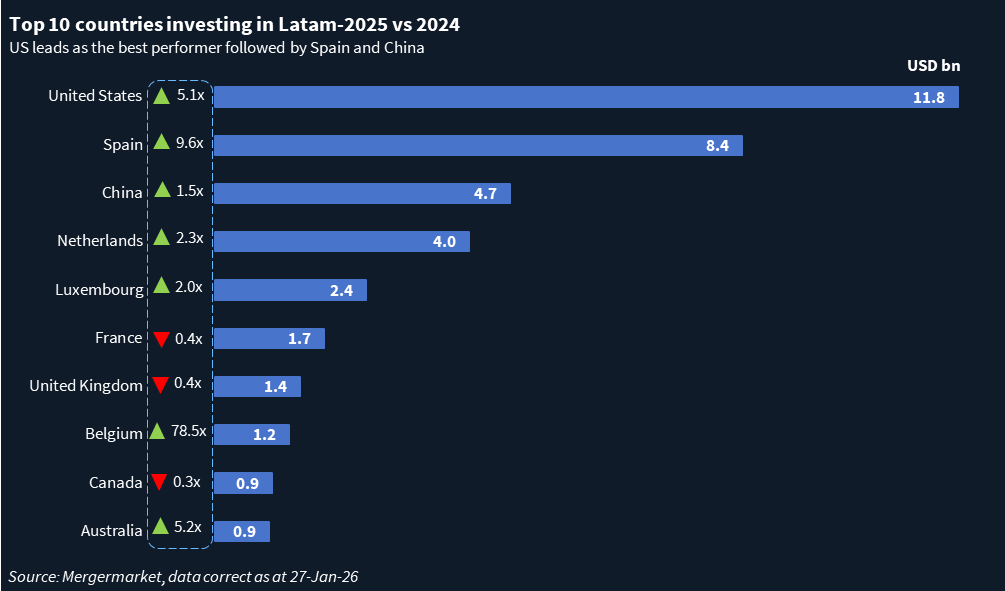

Bank M&A has pushed the value of European financial services dealmaking to EUR 67bn year-to-date, its highest level since 2013, according to Mergermarket data.

Some of these deals, like BBVA’s proposed takeover of Sabadell, announced in 2024 at an equity value of EUR 12bn, and BMPS’s EUR 15bn tilt at domestic peer Mediobanca, announced earlier this year, are hostile bids which may not make it through to completion.

But lenders’ intent to drive deal flow is a marked contrast to years of torpor.

Strikingly, cross-border action is also very much in the mix, despite the risk of political interference and the lower synergies often associated with such deals.

UniCredit CEO Andrea Orcel has made the biggest waves, building a firm stake of 20% in German lender Commerzbank, with a further synthetic position of 9% the bank intends to convert “in due course”.

Austria’s Erste Group announced its EUR 7bn acquisition of a 49% stake in Santander Bank Polska in May; French bank BPCE unveiled its EUR 6.4bn plan to buy a 75% stake in Portugal’s Novobanco last month; and in July, Santander confirmed its agreement to acquire 100% of UK player TSB Banking Group from Banco de Sabadell.

Excess capital, sufficient deal currency

This audacity is driven in part by the healthy war chests banks have accumulated.

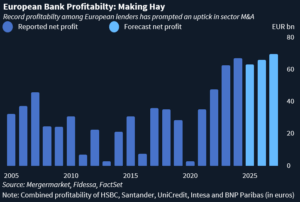

Higher interest rates in recent years have driven profitability, with the top 20 European lenders generating USD 600bn in excess capital over three years, O’Kelly noted.

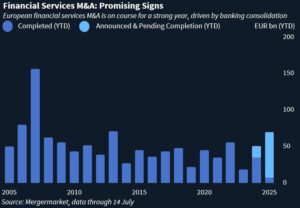

As Mergermarket’s own analysis of the top five European banks demonstrates, higher interest rates between 2022 and 2024 led to an uptick in profits, which are forecast to remain elevated in the coming years.

But the rate cycle is turning, with the European Central Bank’s (ECB) key deposit rate now at just 2% and the Bank of England’s headline rate at 4.25% – and widely expected to come down next month.

This “will lead to margin pressure” and may spur banks to consider how best to capitalise on their recent good run, Anurag Verma, Senior Managing Director at Continuum Advisory Partners said.

A senior Italian banking source, speaking on condition of anonymity, concurred. “Rates are going down, so how are you going to make money? Valuations have been growing steadily – when do you use that?”, this source added.

Banks remain laggards when compared to a wider universe of European stocks, underperforming over the long-term.

But that started to reverse late in 2022 as interest rates began to rise, sparking a near-170% rally in the Stoxx 600 Banks sector on a total return basis. The Stoxx 600 is up 52% over the same period.

Dealmaking could help to sustain that performance.

“We see M&A as an increasingly attractive option to deploy excess capital; most of the deals announced so far in 2025 have promised around double the return on investment compared to buybacks,” O’Kelly said.

Scale hunting

Pursuing scale in the overbanked European market is driving this year’s dealmaking push.

Both BBVA’s bid for Banco Sabadell in Spain, in the face of significant domestic political opposition; and the spaghetti junction of proposed banking deals in Italy, most notably that BMPS move for Mediobanca, demonstrate this hunger for market share.

Further domestic consolidation will be driven primarily by banks outside the top four-to-five in each country, O’Kelly argued, noting “there is an inflection point where scale balances with the costs of technology and regulatory compliance.”

Considerations of technological capability, and reach into adjacent markets, are foremost on dealmakers’ minds when selecting takeover targets.

European banking M&A “is about scale, consolidation and transformation – certain capabilities, areas where you are number one, two, three. You need to be top to be relevant,” Sur said.

UniCredit’s acquisition of Polish cloud-based banking-as-a-service (BaaS) player Vodeno, completed earlier this year, “is a clear example of a deal focused on enhancing tech capabilities and accelerating its digital transformation,” Kirkby said.

A significant proportion of European bank-related M&A is driven being driven by technology, according to Hyder Jumabhoy, Global Co-head of White & Case’s Financial Institutions Industry Group and EMEA Co-head of the firm’s Financial Services M&A Group.

The biggest opportunity in bank-related M&A “is not in balance sheet-heavy, it’s the tech-led side”, Verma agreed. Many banks struggle to manage the level of investment in new technology needed to innovate and scale full ecosystem, BaaS-style solutions, as their starting point is managing legacy platforms, he argued.

Acquiring a digital bank or fintech “could positively support or accelerate a bank” seeking to overhaul legacy infrastructure, Kirkby added.

Yet precisely this barrier also creates some reluctance to buy tech and bolt it on.

“Banks can do their own tech development,” the Italian banking source said, adding it was tough to integrate the PhDs and egos in situ in many tech firms.

Most major banks are more focused on boosting lending capability through deals, rather than chasing speculatively transformative fintech buyouts, Sur agreed.

Such institutions are “unlikely” to make such acquisitions to revolutionise operations, with boards more frequently saying “I buy this player because they are strong in shipping, or aviation, or infrastructure lending – to be stronger and more relevant for the customers in your field,” Sur added.

This is especially the case in a world where private credit has eaten away at banks’ preeminent position in corporate and deal financing lending, Sur said.

Handcuffs off

With banks facing that greater pressure from burgeoning alternative finance, and the threat that US banks will continue to dominate globally as President Donald Trump’s administration reportedly considers loosening capital requirement rules, European regulators have adopted a more accommodative stance to bank mergers.

Europe has little choice – it has “got to find a solution”, the Italian banking source said. “If you look at the economies of scale of investment banking, if you don’t have the critical mass, you can’t have a sector-driven approach,” which makes competing against the US bulge bracket players highly challenging, this source argued.

Recognising the need for scale, regulators across both macroprudential supervision and competition are becoming more flexible and sophisticated.

For much of the time European bank stocks underperformed wider indices, many institutions that had received state support were restricted on their business plans and remuneration policies.

“The handcuffs that were on many of the state-aided and government-supported banks are gone, since these banks have returned to private sector ownership,” Jumabhoy said.

“Big is beautiful is back again,” from a regulatory perspective, as legislators and agencies balance “risk and flexibility to grow,” Sur said.

Nowhere is there greater hope of how this could spur animal spirits than in the codifying of the so-called “Danish compromise” across the EU, which allows banks to add the value of insurance holdings to risk-weighted assets, rather than deducting them from Common Equity Tier 1 capital.

Codified via the Capital Requirements Regulation 3 (CRR3), which came into effect in January 2025, the compromise has been widely tipped to help revive the bancassurance model.

However, the limits of its application appear to have been tested in deals this year for which the ECB declined to approve the compromise. Both BNP Paribas’ acquisition of AXA Investment Managers and Banco BPM’s move for fund manager Anima failed in their attempts to apply the compromise, amid reports of caution about extending its scope too broadly to asset managers.

More positive noises, though, are coming from competition regulators both sides of the Channel in terms of their market understanding, Jumabhoy said.

Both the European Commission, and the UK’s Competition and Markets Authority, have developed their analytical tools and market-specific approach, with RFIs from both agencies containing “a lot of similarities: many of the questions are about the products and demographics, with the regulators bringing in economists to map the market,” Jumabhoy said.

This reflects a greater understanding that a merger could increase choice “if the combined institution can offer a wider range of products to customers at more attractive prices”, Jumabhoy argued.

While acknowledging and heralding this regulatory progress, Sur noted “a number of banks are waiting for [the] level playing field” that would be unlocked by the European Union making progress on its Capital Markets Union and Banking Union initiatives, to truly unify the financial services markets across the bloc.

“Europe needs players of scale to finance defence and other strategic ambitions,” Sur said.

This final, significant piece of the puzzle would drive synergies for cross-border dealmaking to the point they firmly outweigh the political risks of economic nationalism and “huge battles over ATMs, branch closures and union issues”, the Italian banking source argued.

This competitive reality, coupled with healthy balance sheets, is driving a wave of European bank consolidation which could carry well into 2026.

A major prize awaits the EU in delivering on its broader strategic objectives if it can sustain the bank M&A boom by advancing its single market agenda more firmly in financial services.