China buyouts: Investors expect structural change to drive control deals

- Key contributing factors include distress, divestments, succession

- Local GPs are looking to expand value creation capabilities

- Buyouts may help address China’s lingering exits problem

China’s second-largest control transaction, which closed earlier this month, is in equal parts unorthodox and a product of its time. Three years ago, PAG, CITIC Capital, and Ares Management acquired a 60% stake in a shopping mall operator from Wanda Group, which needed capital to alleviate mounting pressures on China’s property sector.

It was a pre-IPO deal, but instead of exercising their redemption right when the listing didn’t happen, the investors rolled over the equity and brought in Abu Dhabi Investment Authority (ADIA) and Mubadala Investment to provide some more. A 60% interest in Newland Commercial Management was now worth USD 8.3bn, up from USD 5.9bn, in recognition of how the business had grown.

More special situations-style investments are expected to emerge as other developers divest assets to pay down debt or IPO spinouts fail to materialise. Yet real estate is only the most conspicuous of China’s pain points.

Amid concerns about slowing growth, geopolitical tensions, and regulatory curbs, founder-entrepreneurs, foreign and domestic corporations, and once expansion-hungry technology giants are contemplating asset sales. Buyouts are unlikely to supplant growth capital in China, but will these forces combine to create a more meaningful control opportunity? Private equity investors are watching on with interest.

“There should be more buyout opportunities available in China,” said Frank Tang, chairman and CEO of FountainVest Partners, which targets China and China nexus deals. “People start their entrepreneurship journey in high-growth markets where there are more opportunities for minority growth capital. As markets mature, more M&A opportunities will emerge.”

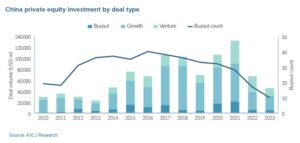

This is not the first time that investors have raised the prospect of more control deals, even though they have never accounted for more than 27% of deal volume in any one year since 2010. Bursts of activity – of different magnitude – have been linked to state-owned enterprise reform, take-privates of US-listed Chinese companies, and multinationals divesting their China operations.

Invariably, a handful of large-cap deals move the needle. China’s top 12 control transactions include US take-privates (Qihoo 360 Technology from 2015 is one of six), a privatisation-cum-succession situation where there was no significant rollover by existing investors (Belle International in 2017) and corporate carve-outs (Reckitt Benckiser’s China infant formula business in 2021).

A few have already proved successful. Focus Media laid down a marker for other US take-privates when it relisted in Shenzhen through a reverse merger 30 months after the initial delisting. Last year, The Carlyle Group agreed to exit its portion of the McDonald’s China carve-out for a 6.7x return.

Categorising control

Carlyle participated in the McDonald’s acquisition in 2017 yet carve-outs have remained part of the China flow. FountainVest bought CJ Rokin Logistics from Korea’s CJ Group shortly before Primavera Capital Group got the Reckitt Benckiser deal. More recently, DCP Capital has picked up China assets from US agribusiness giant Cargill and Canadian health supplements provider Jamieson Wellness.

It is debatable how many more of these deals are still to come. If multinationals are deprioritising China due to concerns about geopolitical blowback and rising domestic competition, they might be keen to sell. But from a longer-term perspective, they are less likely to engage with China in the first place, several industry participants observed.

At the same time, domestic companies are expected to become increasingly active sellers. “Special situations and turnaround opportunities are arising as companies may need to offload quality assets to address financial or debt challenges. Beyond real estate, we see situations emerging in traditional manufacturing sectors,” said Yunge Liu, a partner at law firm Han Kun.

Investors also note that China’s technology giants are looking to offload businesses, driven by a combination of flatlining core operations and regulatory efforts to limit their reach in certain industries. Alibaba Group is identified as a likely seller, following reports that it is seeking buyers for various brick-and-mortar consumer assets.

Founders represent another source of control deal flow, with Charles Ching, a partner at Weil, pointing to a greater cash out “when the business has matured to a point where it would be beneficial for someone with more capital and resources to take the business forward.”

Age – and the absence of successors within the family who want to assume management of businesses – and a more challenging commercial environment are also contributing factors, Liu added. In some cases, entrepreneurs retain a minority interest, which incentivises them to ensure a smooth transition to private equity ownership because they can share in the future upside.

Finally, China-focused private equity firms are increasingly looking overseas for buyouts of businesses that can benefit from exposure to Chinese end markets, supply chains, or technologies. For example, Ocean Link recently made its Japan debut with the acquisition of hotel operator Hotel MONday.

“We are keen on pursuing roll-up acquisitions in Japan’s tourism market as part of industry consolidation,” said Tony Jiang, a founding partner of Ocean Link, who believes there is scope for a new wave of local independent players, having seen a similar theme develop in China.

FountainVest’s portfolio currently features a pallet and packaging business with strong exposure to Australia, a New Zealand-based pet food producer, and a multi-brand sporting goods supplier headquartered in Finland. Tang recently told Mergermarket that he wanted to deploy USD 1bn of equity in Europe over the next 12 months.

Trustar Capital was among the first to pursue control deals domestically, and it looked to do the same overseas as well, running parallel funds that chiefly focused on the US. Most of the time, the GP would team up with US-based peers as the junior partner in deals that involved some China angle.

This partnership approach still rings true. Ocean Link teamed up with Delonix Group – a Chinese hotel group and an existing portfolio company – for the Hotel MONday deal. FountainVest moved for the Finland-headquartered business, Amer Sports, as part of a consortium that included local equivalent Anta Sports, Tencent Holdings, and the founder of Lululemon Athletica.

Tang said that working with strategic investors is not the norm, with LPs the preferred port of call when there is a need for external investment. But he is open to such partnerships on an ad hoc basis if they make sense. “If there is a complementary strategic investor in a deal, we will be more confident in the business case that is relevant to accelerating business growth in China,” he explained.

A capabilities question

These dynamics inevitably draw attention to the capabilities Chinese private equity firms bring to control transactions. Taking a team weaned on minority deals and adding buyouts to the mix – where there is greater emphasis on value creation, industry and functional expertise, and post-investment management – is challenging. Those challenges are accentuated when target assets are overseas.

“Value creation increasingly relies on business operations and synergies. Pure passive financial investors, who typically target minority deals and refrain from participating in the management of their portfolio companies will face difficulty when trying to deliver satisfactory returns in relatively short investment cycles,” said Kevin Wang, a partner of Jingtian & Gongcheng.

“Consequently, those investors are driven to look into acquiring controlling stakes and participating in the operations of portfolio companies.”

He added that more domestic GPs are proactively teaming up with strategic players that serve as sources of capital and expertise. With multiple interested parties, the issue is often alignment. For example, no fewer than eight investors backed the acquisition of a majority stake in a business controlled by A-share-listed Han’s Laser Technology Industry Group. What if they don’t agree?

In this instance, at least all eight are financial sponsors, with IDG Capital holding the largest individual stake of 12.5%. It is far harder to find common ground between financial and strategic investors, according to Terence Foo, co-managing partner for China at Clifford Chance. “They might have different expectations on returns and timeline horizons,” he observed.

Other firms, such as Hopu Investment, favour joint control and forging close working relationships with management teams. “[This] incentivises owners and management to retain a stake and drive value creation in the business. The model offers a balanced structure that allows private equity firms to leverage capital and resources effectively,” said Shaun Lim, co-president of Hopu.

Yet more GPs are figuring out how to reposition themselves to address control opportunities. For example, Oceanpine Capital, previously a growth capital specialist, claims an interest in divestments of non-core assets in Europe. It plans to work with investor consortiums and industry professionals while encouraging existing staff to develop operational skills.

In contrast, ZWC Partners, which is best known as a VC firm, recruited investment professionals with experience in the buyout space. Earlier this year, Firstred Capital hired ex-Alibaba CEO Daniel Zhang as a manager partner, which was regarded as an attempt to deepen operational bench strength – especially in technology-driven transformation – and better address control transactions.

Ultimately, Chinese GPs may seek to replicate elements of the operational approach employed in other markets, but it is not yet a differentiating factor, according to Foo of Clifford Chance. Tang of FountainVest admitted it will be a learning process – especially in terms of closing the management talent gap – and he expects a fair amount of trial and error along the way.

In this sense, deal execution and value creation capabilities are subject to greater scrutiny from LPs when deciding on allocations. “If you don’t have the capacity to add value after gaining ownership, maybe you will be less confident during negotiations and fail to win the confidence of the sellers as well,” one investor suggested. “This could lead to you avoiding certain deals.”

The importance attached to these issues is linked to perceptions around how sizeable the control opportunity can become – and how quickly. Lydia Hao, a managing director of HarbourVest Partners, doesn’t believe the market is at a turning point, which means China has time to develop a buyout ecosystem that encompasses vendor education, GP talent, and availability of leveraged finance.

“It’s constrained at the supply end, with insufficient capital managed by experienced GP talent. But there’s a scenario where if you see more positive momentum in the domestic economy, for example, if real estate troubles begin to ease, the easy money-making mentality could creep back, leading managers back to their comfort zones of minority investing again,” Hao said.

“If so, we would have to slow down the buyout storyline again. We’ve already been talking about it for a long time.”

Exit implications

Regardless, to many industry participants, the rise of control deals is an inexorable long-term trend. It is not only a matter of market maturity; it relates to addressing one of the private equity industry’s fundamental local challenges.

Weakening sentiment on China – as evidenced by a drop-off in fundraising last year, according to AVCJ Research – has a geopolitical dimension. However, this is entwined with concerns about realisations. With the flow of offshore IPOs largely dried up and exits falling below USD 10bn in 2022 and 2023, having averaged USD 26bn in the preceding five years, LPs don’t know when they will get their money back.

By pursuing control deals, GPs no longer rely on the whims of founders when it comes to the timing and mode of exit. There is also a recognition that the growth capital buy-and-wait approach will not deliver the returns of old. “In the past few years, private markets have been like a game of pass the parcel,” a second investor observed. “Now the game is over.”

According to Weil’s Ching, managers increasingly map out exit scenarios before committing to deals. Expected holding periods before a capital markets liquidity event can be achieved and likely acquirers via a trade sale process feature among the items typically discussed, as well as what to do if neither of these outcomes materialises.

“That’s a difficult part, but it’s something sponsors want to ensure they have. In cases where a capital market exit isn’t achievable and selling to another party isn’t an option, they can explore alternative arrangements with other parties to secure a possible exit,” he said.

Even in situations where a private equity firm has secured control, done the operational heavy lifting and successfully implemented value creation plans, optionality around exits can be limited. Hao of HabourVest sees the strategic M&A channel as the missing piece in the puzzle, which has in effect constrained the growth of China buyouts.

“Historically, one could argue it wasn’t as important because the IPO markets were quite open. However, given the current state of capital markets and slow liquidity, IPOs may not be the most attractive option,” she said. “Will there be strategic buyers interested in paying a decent price, perhaps not a high one, for some of these PE-owned businesses?”