UK government bets smaller tidal projects will avoid Swansea’s fate

Lofty costs and the high-profile failure of the massive Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon project has many UK market observers doubting whether the nascent renewable power sector will ever compete with wind and solar.

But the UK government doubled down on tidal last year, awarding contracts for difference (CfDs) for four much smaller projects. The awards are significant in demonstrating the government’s commitment to tidal, and could spark technological developments that will lower the sector’s costs to a level at which they will be competitive with other renewable power sources.

A handful of small, successful projects may also resuscitate investor confidence in tidal following Swansea’s collapse, according to a lawyer active in the sector.

As an island, the UK is uniquely positioned to benefit from tidal power, which is generated when the surge of water during the rise and fall of tides spins underwater turbines. Energy research and consultancy firm Catapult predicts that tidal has the capacity to make up 11% of the UK’s energy needs.

Unlike wind and solar, tides are predictable and can be estimated for centuries in advance, according to a market consultant. Because of its geographic advantages, the UK could become an exporter of energy produced by tidal installations, according to Simon Wragg, commercial director of tidal developer Marine Orbital Power. Wragg believes tidal could be paired with green hydrogen and battery storage as its energy production would be stable.

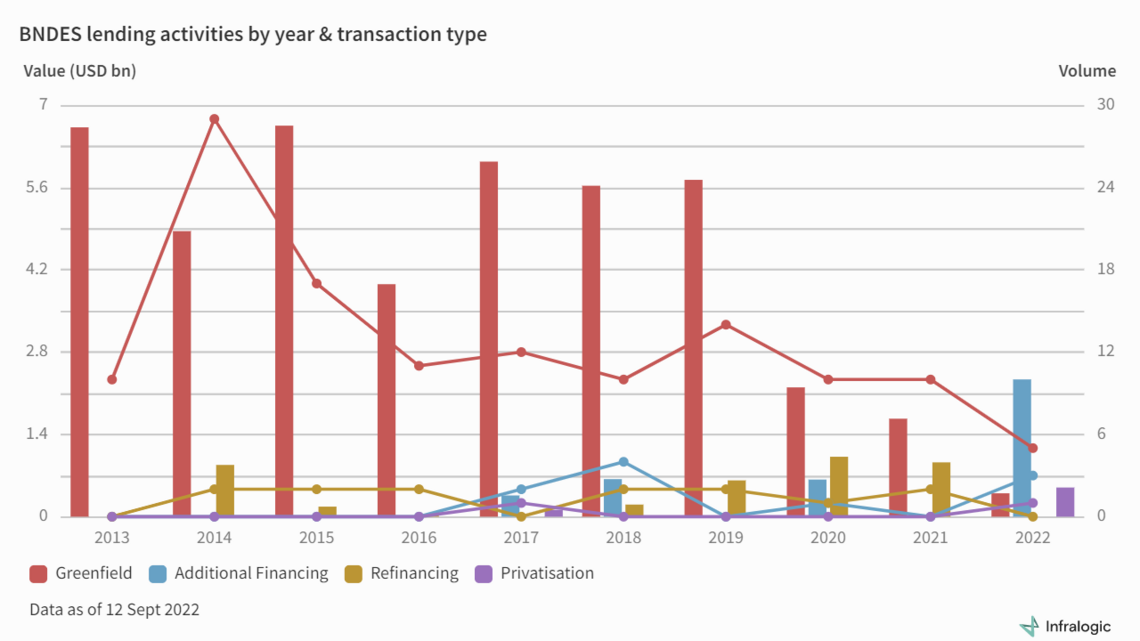

According to Infralogic data, the UK accounts for four of only five tidal deals that have reached financial close; the other is in Canada. The UK also leads in live transactions, with three currently in its pipeline:

But tidal’s advantages and reliability have been difficult to tap. In addition to a high levelized cost of energy, the tidal sector’s biggest albatross might be the failure of the ground-breaking Swansea Bay Tidal Lagoon project.

Swansea sinks

Over a decade ago, the UK government announced plans for a pioneering GBP 1.3bn tidal project in the Swansea Bay area. This project, part of a wider government plan to roll out six projects by 2027, was to have a capacity of 320 MW once completed and use a nascent technology that required developers to build a man-made lagoon. Investors included UK insurer Prudential through its investment arm M&G, and InfraRed, among others.

However, the project has been delayed so many times that the UK government in 2018 announced it would not subsidize Swansea and pulled planning permission from its SPV, Tidal Lagoon Plc. A second attempted market sounding announced by the Welsh government in 2021 failed to gain momentum.

Swansea Bay turned off investors interested in large tidal projects as a lot of money was invested into a project that never broke ground, according to the lawyer. The experience led some investors to question the financial viability of tidal power, and has led other countries to move away from the idea of large-scale projects, the lawyer said.

But the consultant doesn’t see Swansea’s failure as the final ebbing of tidal power, and thinks investors will step up for smaller scale projects — especially pension funds.

The lawyer agrees that a project the size of Swansea may have come too soon, given the new and untested technology it would have required. But tidal technology is developing quickly, and advances may close its cost gap with other renewables — as well as its investor skepticism gap.

Government wades back in

Far from giving up on tidal in the wake of Swansea, the UK government has doubled down in its support for the sector. Many see its 2022 decision to include tidal projects in the UK’s fourth renewables CfD auction as a major step toward supporting the industry.

Under CfDs, or contracts for difference, the government guarantees the price of electricity a producer will be paid. Producers submit competitive bids, with the lowest bid typically winning.

Four projects with a combined capacity of 41 MW were awarded CfDs at a strike price of GBP 178.54/MWh. They include two projects awarded to Orbital Marine totalling 7.2 MW with tidal energy deployments at EMEC’s Fall of Warness site; 28 MW of tidal at the Meygen site in Caithness awarded to Simec Atlantis; and a 5.6 MW tidal energy project at Morlais in Wales awarded to Magallanes.

The CfDs will provide the sector a major boost by demonstrating government support for tidal, according to the consultant and the lawyer. Small-scale projects, such as those awarded via the CfDs, are the best way to give investors new confidence in the sector, the lawyer said.

Still, in the same CfD auction, 7 GW of offshore wind projects were also awarded — a stark reminder that tidal is far from competitive at the moment.

Costs at high water

Also weighing on the sector is the harsh reality that tidal is currently the most expensive renewable energy source in the UK due to the fact that its specialized technology has been deployed on only a small scale. The CfD auction’s tidal strike price of GBP 178.54/MWh is nearly five times that of offshore wind offerings in the same auction, which had a strike price of only GBP 37.35/MWh.

Significant investment is needed to scale this technology up, driving unit costs down.

Tidal costs are expected to fall dramatically in coming decades, according to Catapult. In a report, the consultancy states that tidal energy production costs could fall faster than nuclear per 1 GW deployed and could come to rival those of offshore wind. Catapult estimates that by the time 2 GW of tidal are installed, strike prices could reach as low as GBP 80/MWh.

While CfDs supporting tidal are a big step, the consultant also sees potential problems financing a sector that requires long contracts of 30-35 years. He suggested the government use the regulated asset base (RAB) model which was used by the government in its latest nuclear project, Sizewell C.

Whereas under a CfD, developers bear all of a project’s financial risk in return for its guaranteed strike price, under the RAB model, the risk is shared between investors and energy consumers — with consumers contributing toward development costs via small charges on their monthly bills, according to Norton Rose Fulbright.

The UK has used the CfD and RAB models for its last two nuclear projects. CfD is being used for EDF’s Hinkley project, but the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) opted to shift to the RAB model for Sizewell C. The general view is that RAB offers the more favorable investor terms, as construction risk is shared.

Using the RAB model to develop tidal projects would attract more private investors, the consultant said.