Race to space: India’s revised FDI regulations and Elon Musk’s anticipated visit to give enthusiasts dopamine rush

- Deeper foreign participation, tie-ups with private players expected under amended FDI law

- Due diligence, lack of patent protection frustrate potential investors

The space industry in both India and China was conceived as far back as 1960s.

But nearly seven decades later, India, according to WION, is probably 15 years behind China in terms of technologies today.

With India’s revised foreign direct investment policy that now allows 100% foreign ownership in its space companies (up from a ceiling of 49-70% depending on sub-sectors), and a much-anticipated visit to the country later this year by Elon Musk, who owns the world’s largest space launch company SpaceX, during which he is expected to meet some of the South Asian nation’s space start-ups, enthusiasts in the country’s space technology are getting high again.

“India is capable of coming up with technologies at low costs, and our access to talent availability makes India space-tech stand out,” said Anil Joshi, managing partner, Unicorn India Ventures, a local private venture firm with interest in space technology.

Narendra Bhandari, general partner with Seafund, another local venture capital firm, anticipates strong tailwinds for space-tech investments given demand from defence, agriculture surveillance, telecommunications, weather and mining, among others.

Seafund met around eight to ten space-tech companies in the last six months. These companies are either making different kinds of rocket fuel, building reusable rockets, making space-to-earth communications infrastructures, as well as those that build nano satellites, or produce materials to protect satellites in space.

India is home to a rather fragmented space technology eco-system, with very few private players capable of providing a non-stop solution, from rocket manufacturing to the launch.

In a chicken and egg situation, investments in India’s private sector have also been rather tiny mostly.

The sector gets small-ticket investments, as most private players are still at prototype or pre-product stage, said Sanchit Agarwal, a partner with local law firm Khaitan & Co.

Investors typically flock to a start-up after its product’s commercialization, and only then the company’s valuation will rise, in most cases, he said.

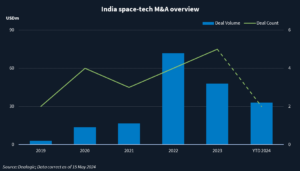

According to Dealogic data, the India space-tech dealmaking took off in 2019, hitting USD 71.7m across four deals in 2022, marking an increase of 330% by deal volume compared to 2021.

So far this year, the sector has sealed two deals worth USD 33m.

By any measure, that’d be considered almost irrelevant compared with what China has achieved.

So far in 2024, China has registered USD 6.9bn worth of deals from the industry, up 16% versus that in the entire 2023, according to Dealogic.

There are 18 Indian companies and 77 Chinese companies in the space-tech segment, according to the data.

In need of bigger cheques

Up to now, the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), a national space agency of the Government of India that basically monopolizes the launch-site operations, has launched 125 spacecraft missions and 96 launch missions, including Chandrayaan-3 which happened in July 2023.

Agnikul Cosmos, a Chennai-based start-up, launched a single-stage technology demonstrator rocket — Agnibaan SOrTeD — on 30 May at 7:15 am Indian Standard Time from Shriharikota, eastern India, according to a Business Times report. That’s the first ever by a private Indian player.

Under the revised foreign investment regulations, foreign players are expected to play a bigger role in India’s space field, including via joint ventures, said Agarwal. Indian space companies can provide their foreign partners support for launching vehicles, or various other services in a cost-efficient manner.

Agnikul Cosmos received USD 26.7m in a round B fundraising in October 2023, backed by US-based Rocket VC and India’s Celesta Global Capital.

Longer term, he also anticipates foreign investments into the space infrastructure market to grow. This is up to now an ISRO monopoly business.

Dhruva Space, which offers end-to-end small satellite construction, launch and monitoring services, is another company worth attention, said Agarwal. Dhruva Space, based in Bangalore, received USD 9.3m in an A-2 series backed by Vietnam’s Bitexco Group and India’s IAN Fund.

According to Dealogic data, the biggest deal ever investment for India’s private space-tech sector was a USD 50.5m joint investment by GIC, LNM India Internet Ventures, and Waverly in Skyroot Aerospace, which designs space launch vehicles.

The majority of it came when Cornerstone Venture Partners Fund, 360 One Asset Management, and Volrado Venture Partners invested USD 33m in NewSpace Research & Technologies.

Anirudh A Damani, managing partner, Artha Venture Fund, a venture capital fund which has invested in Agnikul Cosmos, considers some of the private players as not “investible” due to a lengthy gestation period.

And because of this fragmented market, India has few if any space-tech dedicated funds, Anirudh said.

Another frustration shared by investors in India’s space technology is a lack of patent protection.

Most of the companies started in incubation centers or third-party facilities, says Agarwal. These may create intellectual property-related issues, where the incubation centers chip away at the IP ownership, he says, adding that in some cases, the founders do not hire lawyers while negotiating such contracts, ending up only to cede part of their IP ownerships.

Some players are hesitating in registering patents simply on concerns that may expose their innovations to rivals, though that only poses risks to investors.

Also, Joshi says due diligence into many of India’s private space companies can be rather challenging, as many founders are college students, whose track records can be hard to trace.

As ISRO has been the face of India’s space technology, Joshi reckons private players need to catch up faster so as to enlarge the eco-system.