Prep is key: buyside pours into Haleon and LSEG clean-up sales, but tight block auctions leave investors cold

Blocks are back in business. The huge week for European equity trades yielded extraordinary demand, leading to a rare premium price for the final mega block in London Stock Exchange Group [LON:LSEG], but investors remain unimpressed by underwritten, auctioned, block trades brought at too tight a price.

The GBP 1.6bn sell-down by a consortium of LSEG investors, who acquired their shares following the stock exchange’s acquisition of Refinitiv, was staggeringly priced at a 1.13% premium to close, as a large cohort of sovereign and long-only institutional investors poured into the trade, according to an ECM banker close to the deal. Around half the book went to long-onlies who were willing to pay up for a last chance at a big chunk of stock, given this was a clean-up trade for the consortium.

According to ION Analytics UK Holdings data, Vanguard, Capital Group, BlackRock and Fidelity sat among the top shareholders in LSEG in February 2024, with their stakes growing significantly in conjunction with the various sell-down by the consortium; SWF Norges has also built a 2.19% in the company amidst the various sell-downs.

“LSEG’s premium is not the start of a trend,” said an ECM investor at an institutional buyer. “It was the culmination of a remarkable disposal operation and the sellers were able to get that premium because the earlier trades were structured so well.”

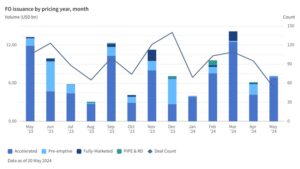

Since the start of 2020, the consortium has disposed of over USD 14bn worth of LSEG stock through various ECM instruments, according to Dealogic data.

Source: Dealogic

The well-flagged, highly open nature, of the sell-downs gives long-only ECM specialists the chance to engage with multiple internal portfolio managers to offer them a chance to buy in size that they would not get in the open market, the investor noted, something which is almost impossible without at least a wall-cross.

The dynamic was similar on a GBP 1.2bn sell-down in Haleon [LON:HLN] later in the week, where GSK [LON:GSK] disposed of its remaining 4.22% stake at a 2.53% discount to close, a PoL ratio of -0.6x the size of stake sold. This was slightly tighter than its last trade in the name, although wider than a March sell-down by fellow shareholder Pfizer [NYSE:PFE] which was able to achieve a PoL ratio of -0.26x the 8.66% stake sold by running a fully-marketed sell-down, rather than a standard accelerated bookbuild.

Most investors in the Haleon transaction were long-only investors, a source close to the trade noted.

According to the UK Holdings data, Vanguard, BlackRock, Norges, MFS Investment Management and Dodge & Cox were among the consumer pharmaceutical company’s top shareholders as of March 31, with stakes rising steadily alongside GSK’s various sell-downs.

The largest change in shares in 1Q was the acquisition of a 0.6% stake in Haleon by sovereign wealth fund GIC, acquiring 55.5m shares over the quarter in conjunction with a 330m share sell-down by GSK on 17 January.

Auction angst

All sources speaking to ECM Pulse this week pointed to the conservative structure of both the LSEG and Haleon sell-down processes as vital to attracting a high-quality cohort of investors.

Last week’s ECM Pulse predicted they would open a window for large equity sell-downs and so they did, with prices shaped by the feedback of investors wall-crossed.

The glowing sentiment around these deals was not reflected in the reaction to a EUR 1.4bn sell-down by Italy’s Ministry of Economy and Finance in ENI [BIT:ENI].

The transaction was mandated after a risk auction, sources said, with three banks, Goldman Sachs, Jefferies and UBS winning the deal. Although the banks did release a covered message, allocations were difficult, which likely led to the syndicate not distributing the full deal.

One source noted that is not uncommon for banks to decide to keep stock back in the interests of securing the best outcome for investors in the deal. ENI’s considerable liquidity meant that it was better suited for the auction model, the sources said. As of around 2pm local time on Monday, May 20, ENI’s shares were trading at EUR 14.82 apiece, only slightly below the offer price of EUR 14.86.

The Ministry of Finance, Goldman Sachs and UBS did not respond to requests for comment on the trade. Jefferies declined to comment.

The dynamics around the ENI trade echo those of an earlier sell-down this year by Germany in Deutsche Poste through KfW, which this news service has previously reported was also won after a risk auction. That stock though has consistently traded below offer price after the deal was priced.

Risk auctions are the opposite of the conservative structure of Haleon and LSEG. Deal timings are secretive, hard to predict, and investors have almost no role in setting a price; even if the seller tries to arrange wall-crossing, feedback on price is often ignored as banks then bid tighter for the business.

While the underwriting guarantees an execution price for the government, risk auctions tend to be largely populated by hedge funds, rather than institutions, and share prices can suffer significantly afterward, especially if banks are left holding shares.

Governments have to get the best price for taxpayers, but there is a middle ground as exemplified by Ireland in its sell-downs in AIB Group [DUB:A5G].

The Irish government typically runs mandated risk trades, according to two bankers. Banks will officially apply for the business but are appointed, rather than bidding the tightest price to run the deals. They will take investor feedback through wall-crossing, or even pre-deal reverse inquiries, and then underwrite a price based on that feedback.

The Irish Treasury did not respond to requests for comment on deal appointment processes.

Deals run like this are far more similar in structure to Haleon and LSEG than they are to ENI or Deutsche Poste and therefore typically attract a higher proportion of institutional investors, both bankers said.

With a host of privatisations expected in the near term, governments are being urged to adopt the Irish model to keep investors engaged in larger disposal programmes over the long run.

Sometimes prudence pays off.