Southeast Asia: a turbulent 2025 reshaping the region’s risk outlook

- US enforcement to target ‘Singapore‑washing’ and hidden China links

- Domestic protests expose political and patronage risks

- Climate disasters amplify environmental and reputational risks for investors

For much of the past decade, Southeast Asia’s growth story has encouraged investors to look past political volatility and regulatory complexity. By the end of 2025, that trade‑off has become markedly riskier.

Escalating geopolitical trade shocks, social unrest, climate‑driven disasters, and high‑profile criminal investigations have exposed the true scale of the challenge of investing and operating in countries like Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, Vietnam, and the Philippines – known as ASEAN-6.

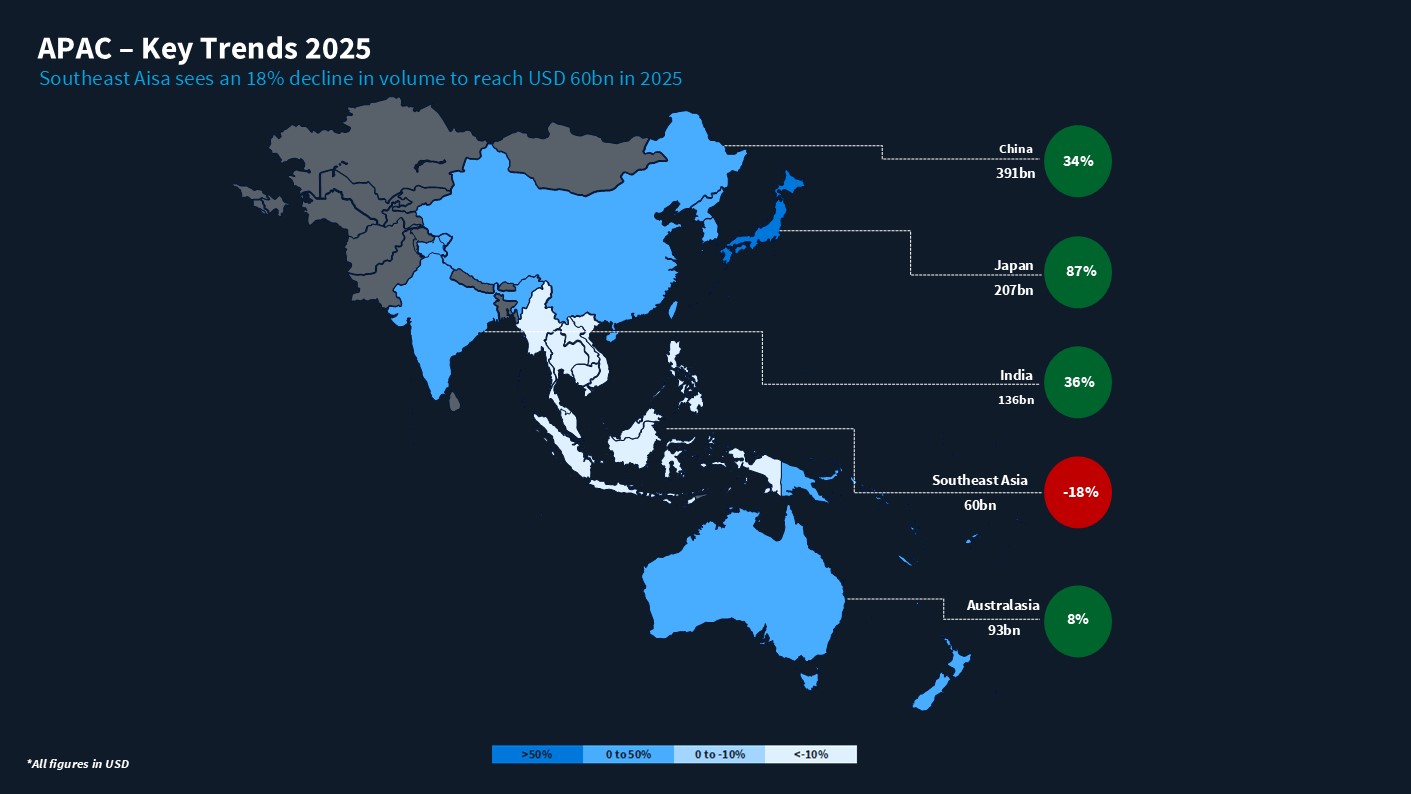

In this context, the region’s M&A underperformance in 2025 stood in stark contrast to the broader Asia‑Pacific rebound.

According to Mergermarket FY25 M&A Highlights, total APAC M&A value surged 33% year‑on‑year to USD 1tn, the highest level since 2021, driven by large‑scale restructurings and take‑private transactions in markets such as Japan, Greater China, and India. Southeast Asia, by contrast, recorded an 18% year‑on‑year decline in deal value to USD 60 bn, constrained by a lack of big‑ticket transactions amid geopolitical and regulatory uncertainty.

This retrospective examines the events that shaped Southeast Asia in 2025 and what they reveal about the compliance, governance, and political risks facing investors and companies looking to do business in the region in 2026.

Shifting Trade Dynamics and Ownership Risk

One of the biggest shocks to Southeast Asian economies last year came on 2 April 2025, or “Liberation Day” as US president Donald Trump called it. The United States announced a raft of reciprocal import tariffs on goods from various countries, including China and the Southeast Asian countries, with the aim of correcting the US trade deficit with its trading partners. These tariffs ranged from 10% to 49% on goods imported from US trading partners and surprisingly included tariffs on goods that are not produced in the US, such as palm oil.

While the US has since dialed back on many of its aggressive tariffs, Liberation Day caused a shift in the dynamics of global trade, and Southeast Asia has been working to ride the changing currents. Multiple countries agreed to increase imports of US goods and reduce tariffs in exchange for the US cancelling or reducing the reciprocal tariffs.

At the same time, these countries are courting alternative importers and investors from China and the European Union in particular. [1] Countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, and Vietnam have also become beneficiaries of companies shifting their manufacturing activities away from China.

In 2026, US authorities may become more sensitive to attempts to dodge tariffs and trade restrictions through so-called “Singapore-washing,” in which Chinese firms set up an intermediary trading company in a neutral country (like Singapore) to keep doing business with US clients.[2] As Southeast Asian countries deepen their economic ties with China, US regulators may also be more wary of any trace of Chinese government ownership in Southeast Asian firms. Finding these links may be more crucial than ever for investors who are looking to work with Southeast Asian companies, especially in critical industries like pharmaceuticals, semiconductor manufacturing, and electric vehicles.

Internally, the deals that the Southeast Asian governments struck with the US to avoid tariffs are also being challenged. In Malaysia, for example, academics and opposition politicians have criticized a clause of the US-Malaysia Agreement on Reciprocal Trade, which was signed in October 2025 and states that Malaysia must align itself with the US on matters of economic restrictions or sanctions.[3] Meanwhile, Indonesia is reportedly backtracking on its commitment to remove non-tariff barriers to US goods.[4]

There is still room for changes and rollbacks as negotiations between the US and its Southeast Asian partners continue. But investors looking to sign major deals with Southeast Asian manufacturers should keep abreast of regulatory changes to anticipate the impact of potential breakdowns in trade negotiations.

Political Unrest, Security Risk, and Regulatory Volatility

Southeast Asia also sustained internal shocks, coming from rising living costs and growing dissatisfaction with government performance. The second half of the year saw waves of anti-government protests in Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, with tens of thousands of citizens filling the streets to air their grievances.

In Malaysia and Indonesia, cuts to subsidies and diversion of government budget to expensive programs such as Indonesia’s school lunch program stoked public anger, despite appeasement measures like cash handouts and fuel price cuts. Meanwhile in the Philippines, corruption that led to dysfunctional flood control projects triggered waves of citizen protest that even gained support from the Catholic clergy.[5]

Regardless of whether the protests lead to positive changes in government policy, they represent a threat to political stability and security. Companies looking to operate in Southeast Asia must account for risks not only to physical assets, but also to employees who may be exposed to unrest or violence.

Major protests may lead to shifting political alliances and cabinet reshuffles, which are often followed by changes in regulatory regimes. Regime changes can also quickly expose once‑favoured politicians to reprisal, with significant consequences for affiliated companies.

In Thailand, for example, the Shinawatra family’s business empire suffered a sharp decline following former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s criminal conviction in 2008 and self‑imposed exile, and the family’s recurring political scandals have continued to hinder efforts to rebuild its fortunes.

Investors should be aware of any links that their target companies may have with politicians and other influential figures and consider whether the patronage they enjoy today may turn into a future liability.

Financial Crime, Sanctions Risk, and Corporate Liability

Some of the most striking headlines from Southeast Asia over the past two years have focused on transnational scam operations, ranging from extortion and romance scams to human trafficking and online gambling.

The victims, some of which hail from outside Southeast Asia, are lured by promises of high-paying jobs, only to find themselves shipped to scam compounds and forced to perform scams or operate gambling platforms, all under threat of violence and torture.

The governments of Southeast Asia have taken action against these scam rings. In particular, the Thai and Myanmar governments have launched bombing runs and raids on scam compounds and casinos.

In November 2025, a court in the Philippines sentenced scammer Alice Guo to life in prison for alleged human trafficking.[6]

Meanwhile, the US government has indicted Chen Zhi, the elusive founder of Cambodian real estate conglomerate known as Prince Group, on suspicion of laundering ill-gotten gains from online scam compounds and human trafficking activities. This has been followed by sanctions and asset seizures against companies in Hong Kong, Singapore, and Taiwan, among other countries.[7] On 8 January 2026, Chen Zhi was finally arrested in Cambodia and extradited to China.[8]

These cases show that as criminals build more complex webs and adopt new methods to mask their activities, they can evade many anti-money laundering measures.

Long seen as a benchmark for both enforcement and ease of doing business, Singapore now faces the reality that its financial system may have been exploited by criminal networks, as underscored by the USD 2.3 billion money‑laundering case uncovered in 2023, which involved illegal online gambling, transnational scams, and unlicensed money lending operations.[9]

Money laundering scandals can lead to criminal convictions and millions of dollars in penalties for any company found to have facilitated the crime. Investors seeking to invest or establish partnerships in Southeast Asia should do their utmost to investigate any possible connections with criminals and sanctioned groups to avoid these ticking timebombs.

Climate Disasters Reveal Environmental Destruction in Indonesia

Southeast Asia is regularly affected by severe weather events and natural disasters. In late November, however, a rare cyclone formed in the Strait of Malacca – the first occurrence since Tropical Storm Vamei in 2001- resulting in significant flooding across the region.

The storm, dubbed Cyclone Senyar, caused more than 1,000 deaths in Indonesia’s Sumatra, with hundreds more casualties reported in northern Peninsular Malaysia and southern Thailand.[10] Thousands were displaced, leaving affected populations vulnerable to further flooding, disease, and food shortages.

In Indonesia, the disaster zones were strewn with thousands of wooden logs, widely suspected to have originated from logging activities (both legal and illegal). The Indonesian government has so far announced the revocation of logging permits for 22 companies in Sumatra, blaming them for logging and forest clearing activities that led to the catastrophic floods.[11]

With higher ocean temperatures, extreme weather phenomena like Cyclone Senyar may increase in the future, leading to greater risk to human lives and assets in Southeast Asia. Forestry, agribusiness and mining companies are especially at risk. They may not only become victims of extreme storm events but may be blamed for worsening the impacts of storms and floods through their business activities.

For example, one company facing heightened scrutiny is PT Toba Pulp Lestari Tbk (INRU.JK), which has been publicly linked to allegations of environmentally damaging forest‑clearing practices and longstanding disputes involving indigenous communities.

The company has been required to suspend logging operations in North Sumatra following directives from the Indonesian authorities.[12] At the same time, its historical environmental and social record has come under renewed scrutiny, even as its owners, the Tanoto family, have directed their philanthropic initiatives towards flood‑relief efforts.

Companies in the extractive industries should aim to minimize the damage they cause to the environment, as it protects themselves against incidents like floods and landslides. Meanwhile, investors should carefully investigate such companies for signs of environmental risk and social conflicts, which may turn into future financial losses and reputational damage.

The events that unfolded in 2025 show that Southeast Asia’s resilience to global headwinds does not insulate investors from material political, regulatory, and operational risks. For investors, the appropriate response is not withdrawal, but enhanced diligence. Thorough background investigations, ownership tracing, and contextual risk analysis are increasingly essential when assessing even well‑known partners in the region.

Blackpeak is trusted by top financial institutions globally, with a specialized due diligence approach to comprehensively assess risks; from discreet investigations to desktop research, industry interviews and site visits. We ensure each opportunity is leveraged for optimal outcomes and delivers to you actionable insights that drive informed decision-making.

Want to learn more about how Blackpeak can help you?

Get expert guidance now by connecting with one of our specialists.

[1] https://policy.trade.ec.europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships-country-and-region/countries-and-regions/association-south-east-asian-nations-asean_en; https://www.asiamediacentre.org.nz/otr-how-southeast-asia-negotiated-lower-us-tariffs

[2] https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/chipping-away-controls-singapore-s-challenge-china-linked-companies

[3] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/nov/05/malaysia-defends-trump-us-trade-deal

[4] https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/10/us-indonesia-trade-deal-in-jeopardy-.html

[5] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2025/10/09/experts-rising-cost-of-living-dampens-income-gains; https://thediplomat.com/2025/09/tracking-conflict-in-the-asia-pacific-september-2025-update/; https://www.asiamediacentre.org.nz/otr-indonesia-philippines-and-malaysia-citizens-rise-against-corruption

[6] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cx2l20jzp30o

[7] https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c70jz8e00g1o; https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/hong-kong-freezes-354-mln-assets-tied-prince-group-syndicate-2025-11-04/; https://eastasiaforum.org/2025/11/29/unravelling-prince-groups-criminal-networks-2/

[8] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2026/jan/08/alleged-scam-kingpin-chen-zhi-extradited-china-cambodia-arrest

[9] https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/billion-dollar-money-laundering-case-recap-cna-explains-conclusion-4401811

[10] https://science.nasa.gov/earth/earth-observatory/senyar-swamps-sumatra/#:~:text=Tropical%20cyclones%20almost%20never%20form,and%20headed%20east%20toward%20Malaysia.

[11] https://www.scmp.com/news/asia/southeast-asia/article/3336516/indonesia-revoke-22-forestry-permits-after-floods-killed-over-1000-people?module=top_story&pgtype=subsection

[12] https://mediaindonesia.com/ekonomi/839614/profil-toba-pulp-lestari-perusahaan-yang-dihentikan-operasionalnya-menyusul-bencana-di-sumatra