Credit Suisse collapse points to future, broader bank stress

Credit Suisse [NYSE:CS] is highly unlikely to be the only European financial institution to be swept up in a liquidity crisis due to macro headwinds, although it is hard to predict who exactly will be next, a variety of financial services market participants have told this news service.

“People knew Credit Suisse was underperforming, but people weren’t expecting them to disappear in a shotgun wedding over a weekend,” said Craig Coben, a former Global Head of Equity Capital Markets at Bank of America.

Swiss regulators successfully leaned on UBS [SWX:UBSG] to merge with its stricken competitor over the weekend, as reported.

There is “no way” that Credit Suisse and US venture capital (VC)-focused lender SVB Financial Group [NASDAQ:SIVB] are going to be the only financial institutions that struggle to cope with an unprecedented set of circumstances, said a European banking executive.

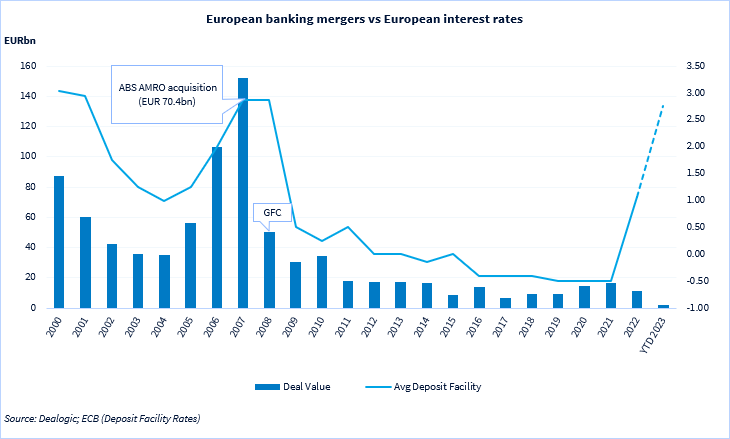

These circumstances include a global pandemic, a land war in Europe, soaring energy prices leading to inflation and hawkish central banks ramping up interest rates.

Regulators misidentified risk at the kick-off of the global financial crisis of 2008-09, Coben said. The subprime mortgage market and the AAA rating of certain mortgage-backed securities was the issue then, he noted.

Now, the problem is primarily government paper, which has no risk of default, but a high risk of loss in an otherwise high-rate environment, Coben argued. Unrealised losses could yet blow a hole in banks’ capital structures if they have to liquidate bonds, he said.

The failure of Credit Suisse is “not random,” said a macro economist at a European bank. “One needs to take this very seriously,” the economist said, adding that “something will break” as interest rates rise further.

The Swiss bank was a “dead man walking,” the banking executive said, adding that it was surprising that Credit Suisse was able to survive as an independent entity for so long after a scandal involving shredding documents allegedly relating to loans to Russian oligarchs last year, as well as the heavy pressures it faced from the USD 5.5bn loss the bank incurred from its exposure to the now failed Archegos Capital Management, and its involvement in the Greensill Capital scandal.

There are thousands of financial institutions and at least some of them will have mismanaged liquidity, the banking executive said. At least some private equity firms and asset managers could also be at risk, the executive added.

However, there are other respects in which the circumstances are very different from 2008, according to a partner at a US law firm in the City of London. “Europe’s banks have stronger balance sheets and are generally better capitalised,” the partner said.

European regulators have been preparing legislative tools since the last major crisis, which means they can intervene quickly and effectively, the partner said. “The question which will be answered soon enough is whether those tools will prove robust enough to protect deals struck at short notice and give market participants confidence that contagion risk should not be a concern. Watch this space…” he said.

One major milestone in the months ahead will be the European Central Bank’s (ECB) EU-wide stress tests, due in July. Banks with at least EUR 30bn in assets will be included in the exercise.

But central bank stress tests focus on asset quality and less on withdrawals, which have scuppered both SVB and Credit Suisse, Coben argued. “Hold-to-maturity is fine ’til you have withdrawals,” he noted. In other words, if banks are having to liquidise bonds to fund withdrawals, some degree of balance-sheet repair becomes inevitable.

High CET1 ratios may not be enough to save banks from stresses in this environment. Credit Suisse’s latest reported CET1 position was 14.1%. “It’s about vulnerability to withdrawals,” Coben reiterated. Some Eurozone banks may have different types of depositors to Credit Suisse, which may in theory make them less susceptible to a run, but this would have to be looked at on a case-by-case basis, he noted.

This need not necessarily mean rights issues, “it could take a lot of forms,” Coben noted.

One form exercised by Swiss authorities this weekend is – in an emergency setting – to force a merger. However, “putting a good bank and a bad bank together doesn’t always work,” one banker said.

The 2009 merger of HBOS with Lloyds Banking Group [LSE:LLOY] was mentioned by several market participants as a warning from history. The UK government subsequently had to inject cash into Lloyds.

However, UBS’s management has learnt from the experience of financial crisis-era acquirers to drive a hard bargain even when the regulator asks you to do a deal, Coben said. Swiss regulators have agreed to provide CHF 25bn (USD 27bn) of downside protection above a CHF 5bn threshold and wrote down some CHF 16bn in Credit Suisse contingent convertible AT1 notes as a capital buffer.

A lot hangs on what UBS finds when it looks through Credit Suisse’s derivatives holdings and Asia-Pacific book, Coben said. “It could be a great deal, but there are a lot of unknowns,” he said.

Data by Marie-Laure Keyrouz