Infralogic insights: foreign investment in APAC infra to continue growing

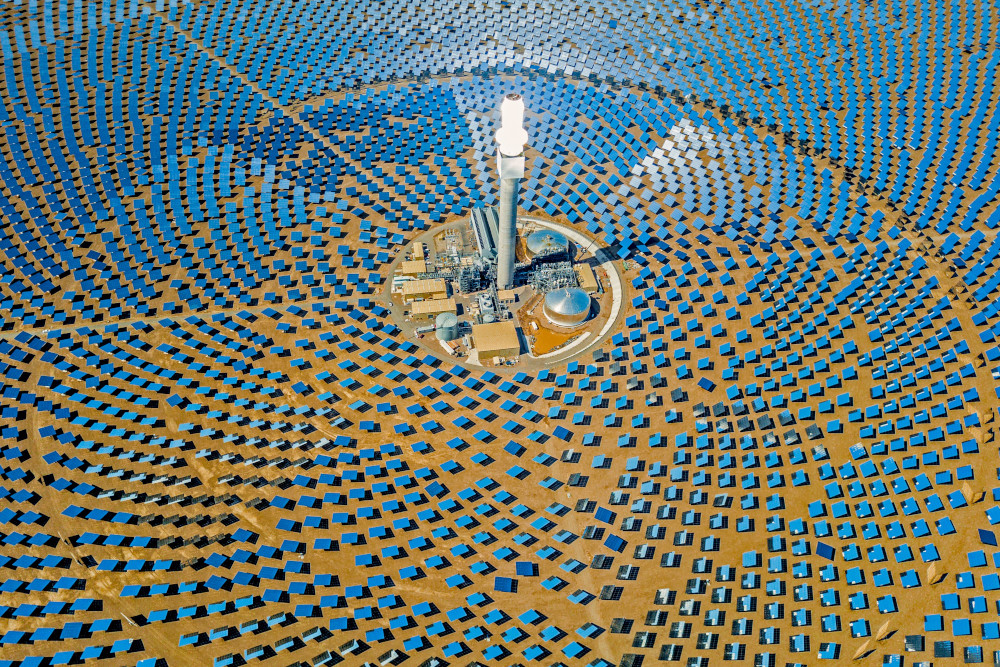

Foreign investment in APAC infrastructure assets will grow exponentially in coming years, continuing a recent growth tack as international investors pursue plentiful opportunities in a region with an active financing market and strong government support for renewables, according to several sources.

Foreign direct investment (FDI) in developing portions of Asia rose by 19% in 2021 from 2020, led by an increase in renewable energy project financing, according to The World Investment Report published by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

“Mega-regional efforts are likely to boost further cross-border investment,” said James Zhan, UNCTAD’s director of investment and enterprise, in the report.

To be sure, the APAC region is not immune to the factors that have slowed infra investment activity in other regions, including concerns about inflation, rising rates and the supply chain crisis. Most market players say they are sticking to their strategies despite inflation, according to a recent survey conducted by Infralogic. But one APAC-based investor who manages more than USD 10bn in assets said that “increased inflation would negatively impact [the] local private project financing market,” when asked about headwinds.

Most, however, expect foreign and cross-border investment to continue apace in the region.

Case study: Taiwan

One example of growing APAC FDI is Taiwan, where foreign investment into the energy sector has averaged USD 750m annually since 2019 — prior to which it was largely non-existent — according to data from Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs.

The influx is also reflected in Infralogic data, which show the average annual value of renewables deals growing to USD 6.58bn in 2018-2021 from USD 465m in 2016-2017 — and that foreign developers dominate the island’s private infrastructure and energy markets:

The growth in FDI can be in part attributed to a significant policy push by the government towards renewable energy, which began in 2016 with basic installed capacity targets — but grew more comprehensive in subsequent years with additional regulatory regimes such as those surrounding feed-in tariffs (FiT) and the identification and distribution of development zones.

Taiwan’s Bureau of Energy recently said that bids received for the most recent Phase 3 offshore wind auction totaling 3 GW came from “global investors and renewables developers from Europe, North America, and Asia,” and well exceeded targets, as reported.

The Formosa 1&2 and Hai Long 2&3 offshore wind projects, totaling nearly 1.5 GW of installed capacity, attracted notable investments from foreign powerhouses Macquarie (USD 900m), Stonepeak (USD 2.7bn) and Northland Power (USD 5bn).

Project financing models are evolving in the region. Foreign developers are deploying more mature financing methods and looking at full capital structures. An example is the “Ørsted model” employed for the holdco financing of the Greater Chuanghua 1 Offshore Wind Farm (GC1), said Jason Humphreys, co-head of Allen & Overy’s Energy, Infrastructure and Projects practice in APAC, who advised on the project.

In an Ørsted model, developers deploy initial investments for the project using their own equity. They then refinance the investments at the holdco level after forming a joint venture with other investors — typically institutions or funds.

Taiwanese offshore wind projects rely heavily on local currency financing, tapping the active local banking market to satisfy requirements for local participation, Humphreys said.

“We have seen that both Taiwanese commercial lenders and local life insurers are active in some of the financing deals,” he said.

Infralogic data show that over USD 5bn of the USD 13.2bn in total debt issued for offshore wind projects in Taiwan to date has been sourced from domestic institutions — suggesting adequate future capacity.

For instance, 16 of the 20 banks that have participated in CIP (49%) and China Steel’s (51%) financing last year of the Zhongneng Wind Farm project were local Taiwanese lenders.

Not so easy

Competition between foreign developers to partner with local conglomerates is fierce, Humphreys said. “They [the local conglomerates] don’t necessarily need a passive financial investor to only provide financial support,” he said. “What we’re tending to find is that there are greater opportunities for investors who can bring something to the table.”

Foreign investors need strong capabilities in “technology, operating experience or access to new markets or customers,” Humphreys said. “To successfully team up with a local entity, you need to really understand your partner, especially in countries with investment restrictions limiting foreign ownership or control in certain sectors or on land ownership (depending on the jurisdiction).”

Some say the competition is growing, with local entities catching up in technology.

Blackrock sees large foreign conglomerates initially dominate and drive nascent renewables markets, but eventually local contracted players become quite talented, especially in Vietnam, according to Valarie Speth, managing director of BlackRock’s APAC Climate Infra Group, speaking at the Infralogic IIF forum in Singapore in July.

Those local players are showing the potential to scale-up and reach international standards if they receive the right capital, technology and development expertise, she said.

Government policy and regulations also play a role.

“If there is an election coming up, or if there has just been an election, the market may need to adjust for regulatory changes, resulting in a decrease in deal flow whilst that is worked through,” said Humphreys. “Similarly, you sometimes have people elected who are less supportive of FDI than their predecessor or changes in policies, so these factors can influence investment appetite.”

The appetite for FDI varies widely by country, according to Simon Wilson, renewable energy general manager at JERA, speaking during the IIF Forum. “There are still different layers of commitment in each market as to the amount of foreign investment they want,” he said. “If you look at Vietnam, it’s very clear they want more localized players to … drive the growth of the industry.”

Getting there first

There is a first-mover advantage to investing in some markets, according to Humphreys

“To the extent that people see opportunities in new markets … they will be keen to secure a first mover advantage to secure the best opportunities, partners and sites and the likely higher returns as a market first opens compared to as it matures,” Humphreys said.

While the current economic environment has sent some investors to the sidelines, opportunities abound in APAC for those with longer-term investment horizons.

“You might have to invest now [in order] to be ready once [opportunities] unlock,” Speth said.